Film review by Jason Day of Tartuffe, the German silent drama starring Emil Jannings and Lil Dagover. Directed by F.W. Murnau.

Silent

Synopsis

A young, care-free actor (Mattoni) returns home to his rich grandfather (Picha) but the old man is under the control of his devious housekeeper (Valetti). The garrulous woman promptly has the young man thrown out. Resolving to help the old man see who she really is and get rid of the manipulative hag, the actor poses as a passing mobile cinema operator who visits people’s homes to screen films for them. The film he shows is Tartuffe, biased on the play by Moliere, about a fake evangelist (Jannings) who, like the maid, inveigles his way into the affections of a susceptible man (Krauss) in order to take his money and possessions and his beautiful wife (Dagover). But the loyal wife hatches a plan with their maid (Hoflich) to trap him, mirroring the events in the modern day.

Review, by Jason Day

Sandwiched between the awesome multi-million Rentenmark phantasmagoria that was his version of Goethe’s Faust and his subsequent poaching by the Fox Film Corporation to make films in Hollywood, Tartuffe is often referred to as the forgotten or neglected Murnau movie.

But anyone who has patiently sought out this satisfying nugget of wonder will know this is not the case. Where Murnau is more famous for focusing on either eye-popping spectacle (Faust), creepy horror (Nosferatu) or haunting landscapes (City Girl, Tabu) here he uses his camera to fixate in the intimacy of the human face and expression. He allows this skilled silent cast to weave a cinematic spell, rather than deploying his usual bag of magic tricks.

Murnau reveals himself to be in a playful, more sarcastic mood than usual – Mattoni mouthes directly at the camera to announce how he will right his poor, wronged grandfather, smiling broadly as he sets the scene. A teasing tale of two clearly distinct halves unfolds; the parlour tale introduces us to themes that will be explored in more witty depth in the boudoir tale of the past.

Cameraman Freund and the designer personnel worked with Murnau to experiment and underline the contrasts. In both, there is a gluttonous reliance on huge close-ups. In the modern tale these are used to scan every wrinkle and blemish of the characters, the actors being shorn of make-up and photographed in a flat, ugly light. Freund also uses several sharp, jolting ‘angles’ throughout these sequences (note how the camera rests on the floor to capture the old man’s shoes being moved).

For the film of Tartuffe, the sets are crisp white and cream, the actors are caked in glamorous, ‘Hollywood’ make-up, Dagover’s costumes are sumptuous and the flattering, soft-focus photography makes all of this glisten like the make believe dream being projected. For both halves though, the use of fake depth backdrops are used.

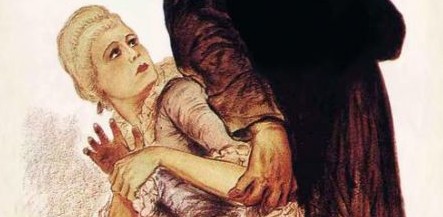

Despite the almost ‘back to basics’ that one of most technically innovative of film-makers has chosen, there is still some ingenious camera jiggery-pokery on show. A miniature of Orgon is magnified when Elmire’s solitary tear drops on it, seeming to course and caress over him, as she longs to do again with her husband, tantalisingly at arms length. Later, as Orgon peeps from behind the camera at the first trap his wife sets, Tartuffe sees him in a grossly distorted reflection in a silver jug. After Tartuffe uncovers Elmire’s plot to catch him out, he strides in judgement reading his bible, underneath an enormous dual headed lamp that resembles scales of justice. Elmire flirts desperately with him to cloak her duplicity.

It hardly needs dwelling on then that this duality is mirrored throughout by this play acting: the grandson pretends to be someone else, Tartuffe is the falsest of prophets, Elmire stoops to any false depths in order to rid her house of him. The curtains deployed seem at first like just a backdrop, obscuring the protagonists from each other but also allowing them to focus more clearly (Grandad on the film being projected when his drapes are shut; Orgon can spy on his friend as his wife turns honey-trap spy).

Jannings, as one would expect, puts in his usual exaggeratedly entertaining characterisation, a comical hypocrite permanently buried in the tiniest of bibles, with a permanent squint. His piggy, calculating eyes are forever surveying whatever is before them for valuation, for sustenance (he keeps one eye firmly shut even when gorging himself at breakfast), monetarily (quickly pinching Orgon’s ostentatious ring and squirrelling it away in his pocket) or sexually (eyeing up Elmire’s buxom breasts over his omnipresent bible, later tapping them moralistically with it).

Pointedly with the last title card, Murnau speaks through the grandson character when he asks us if we know who the hypocrites are in our life. They could be sat beside us, even while we enjoy this satisfying Chinese Box of delights. Murnau, a homosexual, who frequently touched on elements of sexual and religious hypocrisy in his work, asks his audience a serious question hidden by Mattoni’s coy smile. Duality and playfulness to the end.

Credits and Cast

Director: F.W. Murnau. Ufa. (U).

Producer: Erich Pommer

Writer: Carl Mayer.

Camera: Karl Freund.

Sets: Robert Herlth, Walter Rohrig.

Music: Giuseppe Becce.

Emil Jannings, Lil Dagover, Werner Krauss, Lucie Hoflich, Andre Mattoni, Rosa Valetti, Hermann Picha.