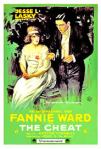

Film review by Jason Day of the silent film thriller about a society woman manipulated into being unfaithful. starring Fannie Ward and Sessue Hayakawa, directed by Cecil B. DeMille.

Director: Cecil B. DeMille. Paramount (Not rated).

SILENT

Cast & Credits

Producer: Cecil B. DeMille.

Writers: Hector Turnbull, Jeanie MacPherson.

Camera: Alvin Wyckoff.

Music: Robert Isreal (1994 reissue).

Sets: Wilfred Buckland.

Fannie Ward, Sessue Hayakawa, Jack Dean, James Neill, Yutake Abe, Raymond Hatton.

Synopsis

A silly, hedonistic society, East Coast of America socialite (Ward) takes the proceeds of a charity fund-raiser she organised and puts it in a dodgy investment. When it falls through, her handsome and rich Asian pal Hayakawa bribes her with money to make up the short-fall…if she will have sex with him. The die is cast for a social scandal with no compare.

Review, by Jason Day

The young Cecil B. DeMille was a stage actor and playwright who turned his hand to film directing just before the start of the First World War, incidentally directing the first ever movie in the then sleepy Californian orange-growing hamlet of Hollywood, The Squaw Man (1914), a huge success that he would go on to remake twice.

Although famous for his sprawling, mostly biblical, epics DeMille was an experimental and innovative director/producer at this point in his career, not afraid to take a few risks and try out new ideas, this being a point in film production when everyone was influencing everyone.

The Cheat, regarded as quite avante garde at the time is a typically hoary old theatrical melodrama, the type of story that might have titillated the early tabloids and, given that the female lead is the archetypal, frivolous East Coast society trophy spouse one might see in Real Housewives of New York, could still grab a few headlines to this day. Just for good measure, the plot also includes the then largely taboo subject of miscegeny. Ward toys with her handsome Asian admirer and there is even an interracial kiss (though the script allows for Ward to have passed out for this).

From the outset we see the type of silly woman Ward is. Trying on an expensive coat as her husband tells her to rein in her extravagances, she petulantly slamming the phone down on him. This leads to what might be the first ‘whatever’ moment in cinema when she shrugs her shoulders in annoyance. Neglected by her workaholic but devoted husband (Dean), she prefers to gallivant the night away rather than pay her loyal maid.

It was fitting that Ward was selected for this, her most famous film role. Noted off-screen for her slavish devotion to looking youthful, she had the right air of frippery and looks remarkably well-preserved for a woman of 43, even with the heavy make-up that was used in movies at this time. Her acting is actually quite delicate and amusing, sensual even, only hitting the neurotic high gear beloved of silent film actresses during the court room scene when she ‘fesses up and practically flings herself at the Judge’s mercy.

Hayakawa is a demonically exotic leading man (see New York Times bio here). More famous now for his performances in much later, sound productions such as Bridge On the River Kwai (1957) and Swiss Family Robinson (1960), he was at this point that rarest of things, an Asian actor who achieved considerable fame in front of the camera in early Hollywood. Of course, this achievement was only established through the prism of racism as he would usually play debauched, hedonistic or rapacious Oriental men, hell bent on seducing his white, female co-stars. Here gives a relaxed and louche performance as a man who stoops to blackmail to sleep with Ward but is also at ease in the earlier scenes when he is a respectful and almost romantic playboy friend.

DeMille’s style and flamboyance are easily spotted. Ward’s extraordinary ‘Bird of Paradise’ hat in the opening scene shows his penchant for memorable millinery (one need only glimpse his later films with star Gloria Swanson to see where he was headed).

His love of crowd scenes are also evident. From the Red Cross Bazaar fundraiser and the later court room, they are smaller in scale and there isn’t the cohesive beauty of en masse movement in his later epics when small towns of people followed his megaphone dictates, but there is neatness and order to them.

Sexuality is explored too, within the confines of a respectful, religious director’s personality (DeMille was a strict Episcopalian). The attempted rape and branding scene are surprisingly aggressive.

But the reason why The Cheat is infamous and a well thumbed reference point in most cinema history textbooks is for the use of stylish and recognisable camerawork.

The establishing scene has Hayakawa burning incense and it is clear that the cinematography has a unique, moody quality. The background is dark but criss-crossed with light, his face is illuminated by the light of the burner underneath him, chiaroscuro being the technical term.

When Ward’s husband discusses a financier’s perilous financial situation, she sees them in silhouette on the other side of a Shoji screen, a shadow discussion. The next shot is clever; she and Hayakawa are isolated by darkness as an imagined newspaper headline announcing her guilt is spotlighted above her. Her fate is sealed not necessarily by her thoughts or actions, but with this cinematic device.

Later, as Hayakawa waits for Ward to give in to him, his house is sparsely lit and a Bansai tree’s branches stretch out with grasping, constricting finger-like shadows.

The borders of light against shadow prefigure the key elements of what would become film noir in the 1940’s, but up until then would denote expressionist and then crime films.

Such tonal contrasts reflect the type of film we are watching, literally the good against the bad and help DeMille to continue the theme during key moments (the evening wear of the stuffy society ball Ward attends, her prim white dress in direct opposite to her racy, lacy black attire when at the more relaxed, society mixer during the film’s first scene. Cigars and brandy, versus cocaine and bubbly.

Even during the court scene the parallels are still there: Hayakawa sits waiting for justice with two asian friends, the jury is entirely comprised of white men.

The camerawork is exquisite but in all, doesn’t actually swamp the story, the style is utilised at key events in the narrative to highlight the action, rather than swamping it in semiotics.

Reblogged this on Cardinal Rules for the New Entrepreneur.

LikeLike

Thank you for re-blogging! Hope you enjoyed the review, clever little film that deserves to be more widely seen.

LikeLike

The Cheat is a silent that I have yet to see. I will be looking for it to play, on TCM’s Silent Sundays.

LikeLike