Director: Alfred Hitchcock. British International Pictures (BIP)

COMEDY

Producer: John Maxwell. Writers: Alfred Hitchcock, Eliot Stannard. Camera: John J. Cox. Music: Mira Calix (2012 reissue). Sets: Wilf Arnold.

Betty Balfour, Jean Bradin, Ferdinand van Alten, Gordon Harker.

SYNOPSIS

Spoiled heiress Balfour defies her father by running off to marry her handsome but poor lover (Bradin). But Daddy (Harker) has a few tricks up his sleeve to show his daughter who is in control.

REVIEW

Hitch’s effervescent silent comedy stars the irrepressible and mostly adorable Balfour (so called the British Mary Pickford, though here she’s far gamier and raucous than eternal child of the screen Pickford ever was) and is as delightful as the bubbles up your nose that champagne itself can bring.

Hitch was never the master of comedy, but when he attempted one they were clever and efficiently produced. Champagne is an of-it’s-time frothy confection on the surface, but underneath runs a vein of cutting social observation. Hitch’s sly swipes at the frivolously hedonistic ‘It’ girls of the day have more than just a whiff of mendacious commentary. Perhaps this explains the ‘fun’ that comes from the storyline as Balfour is hoodwinked by all around her, veritable torture for such a flibbertigibbet.

His attention would always be on the visuals and there is an awesome opening shot, as a champagne bottle’s cork and contents explode over the camera, cutting directly to the point of view of a club reveller downing a glass of bubbly, the dancers in front of him magnified through the side of the glass. There is an ingenious trick shot later, aboard a rocking ocean liner, the crew lurching to and fro in perfect unison. Later, Balfour appears to whizz in and out of Bradin’s view as he succumbs to sea sickness.

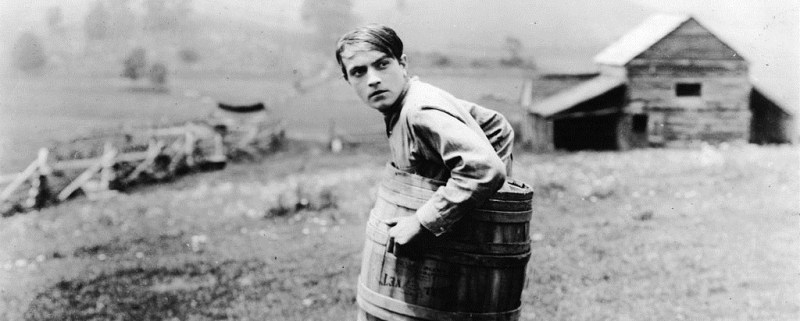

Balfour has buckets of charm as the original 24 hour party girl. Bradin is good looking but otherwise vacuous as the socialist minded boyfriend whom she adores.

This reissue, from the British Film Institute, features an intriguing, other-worldly score from Calix, who herself described her music as “psychedelic”. Audiences will certainly agree; it may take a little getting used to. It’s interesting to note how a different score can totally change the meaning and appreciation of a silent film. Calix makes eerie use of violins during the opening, as shrill and nerve jolting as those Bernard Hermann would utilise in Hitch’s Psycho (1960). It is a slightly epileptic modern jazz, almost discordant but never displeasing, like a pleasant hangover. The original vocals, by the Juice vocal ensemble, are almost a sibilant wail and veer from Madonna’s ‘Papa Don’t Preach’ to Pink’s ‘Get the Party Started’, suitably complementing the kooky acoustics.

A tasty and satisfying vintage that has been made glorious for modern eyes and ears.